December 01, 2025

by Daniel Vesecky

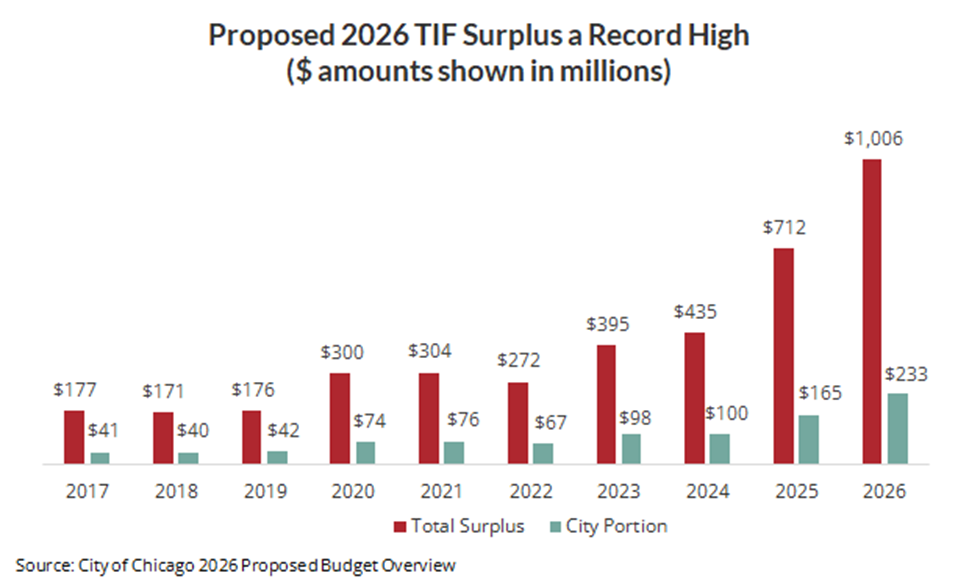

In October of 2025, Mayor Brandon Johnson released his proposed 2026 budget, which aims to close a deficit of over $1.2 billion as is required by state and municipal law. One component of the budget is a $1.01 billion Tax Increment Financing (TIF) District surplus, which will generate an estimated $232.6 million in revenue for the City of Chicago (Chicago or ‘the City’). TIF districts are supposed to segment and dedicate a portion of property tax collections within a designated “blighted” geographic area to fund economic development and capital or infrastructure projects. State law mandates that any excess funds in each TIF district be released from the fund and distributed annually to all local government entities within Chicago—a process known as a surplus. The City of Chicago declares the total TIF surplus, and the Cook County Treasurer distributes it to taxing agencies based on their share of total property taxes billed. As with the rest of the proposed 2026 budget, the TIF surplus must be passed by the Chicago City Council before it becomes law and is executed.

The City receives approximately 23% of the surplus, with approximately 55% going to the Chicago Public Schools (CPS). The remainder is distributed between Cook County, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD), the Cook County Forest Preserve District, the Chicago Park District, and the City Colleges of Chicago. Based on the proposed surplus of slightly above $1 billion, Chicago is slated to receive approximately $232.6 million, while CPS will receive approximately $552.4 million.

Chicago’s TIF surpluses have been steadily climbing since they became a regular occurrence in the mid-2010s. The proposed $1 billion surplus would be the largest in Chicago history, significantly more than the 2025 surplus of $712 million.

There are several reasons for the year-to-year growth in TIF surplus. First, due to the underlying mechanics of TIF districts, they take in a larger portion of local property taxes each year as property values grow. Chicago created most of its 108 TIFs in the late 1990s, and they are now disproportionately nearing the end of their life cycles, when the growth in property value within the TIF is producing the highest taxable revenue. The resulting property tax revenue stream has grown significantly in recent years, leading to more excess funds available to use as surplus.

Additionally, the City changed its TIF surplus policy in 2025. According to the City’s budget office, alders could previously hold funding for projects that are still in the planning process and have not been submitted to the City. Such holds could extend for an indefinite period of time. Under the new policy, holds can only be made for projects that are almost ready for submission to the City, and funding can only be held for a maximum of one year. This change freed up some previously held project funds for immediate surplus and generated an additional one-time windfall.

How is the Surplus Determined?

TIF districts range massively in size, with the largest, such as the Kinzie Industrial Corridor and LaSalle Central TIFs, generating well over $100 million in property tax revenue annually, while some very small TIFs yield less than $1 million in annual revenue. When determining how much money to surplus from each TIF, the City follows a policy summarized in its budget. That policy requires the City to determine the total amount of funds in the TIF district that are not obligated for approved projects or held for projects that have not been formally proposed. Of that total, all funds above $2.5 million are designated part of the surplus, and “the City declares 25 percent of the balance over $750,000 [to be surplus], progressing up to 100 percent of the balance over $2.5 million.” This practice, known as a “TIF sweep”, means that every TIF is left with a small amount of excess funds.

There are three exceptions to the standing policy. First, TIFs that will close in the coming year are fully swept, as there is no need to hold funds in them for future projects. Second, TIF districts in the downtown area sweep all available funds each year. Finally, TIF districts designated as “neighborhood TIFs” are fully exempt from the annual surplus until they close. These TIFs are typically geographically small and have low annual revenue, so they must build up multiple years of revenue to fund development projects.

The City’s policy change to reduce the size and scope of holds for unsubmitted projects frees up previously held funds for this year’s surplus. Although City data does not make clear how much of the $1 billion surplus is accounted for by this change, it is likely partially responsible for the significant increase between the 2025 surplus and the 2026 proposed surplus. It is important to note that funds freed up from such holds will not replenish in 2026, making this revenue bump one-time in nature. This makes it likely that the 2027 TIF surplus will not continue growing at the same rate as it has for the last several years.

Where does the Surplus Come From?

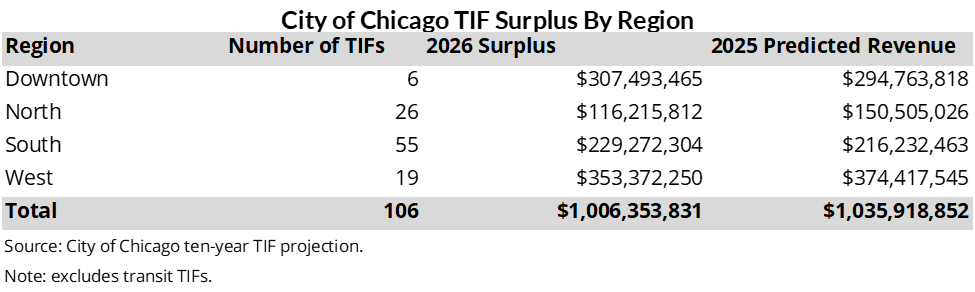

The following table breaks down the surplus by region within the City. The size of the TIF surplus from these areas largely mirrors where TIFs are most concentrated.[1]

The largest contributors to this year’s surplus are the West Side and the Downtown area, with significantly less TIF surplus coming from the North Side. This is because the North side has far fewer TIFs than the rest of the City. A large portion of the North Side is covered by the Red-Purple Modernization TIF, but this TIF is only used for transit projects and is not being swept for surplus this year.

The following map shows the locations of all TIFs within the City of Chicago (excluding transit TIFs), along with their annual revenue and proposed surplus totals for 2026.

The Future of TIF Surplus

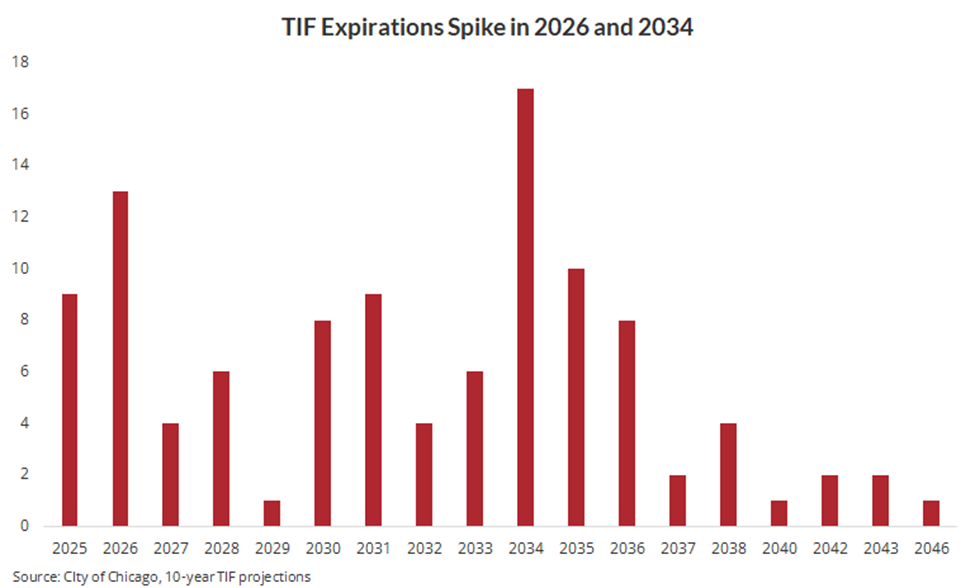

The size of the annual TIF surplus numbers has grown every year since 2017. The City’s many TIFs continue to age, resulting in property value growth over time, and thus increasing property tax revenue. Though that will continue to be the case for the next few years, the high level of revenue from aging TIFs will begin to taper off in the coming decade as TIF districts expire. Nine TIF districts are set to expire this year, and 13 more will expire at the end of 2026. By 2036, only a handful of current TIFs will still exist. This means that TIF surplus levels will decline significantly.

When a TIF district reaches the end of its 23-year lifespan (or 35 years if renewed), the equalized assessed value that had been frozen at the TIF’s creation is added back into the pool of property value that is taxable by local governments (i.e., the tax base). Each taxing body may then increase its overall property tax levy by applying the existing tax rate to the new base in the year after the TIF expires. This permanently increases the total property tax levy. Importantly, this revenue does not count toward the annual property tax increase limits for non-home rule governments set by Illinois’ Property Tax Extension Law Limit (PTELL). Therefore, although the closure of TIFs will consequently reduce the TIF surplus that the City and other local governments take in each year, these governments will be able to make up the difference by levying additional property taxes.

Conclusion

While the City of Chicago has benefited from increasingly large TIF sweeps in recent years, TIFs were not designed to serve as a source of operating revenue for local governments, and TIF surpluses of this size will not necessarily continue in the future. Particularly in the past few years, the TIF surplus process has played a revenue-generating role for the City of Chicago and other local governments, resulting in an annual process that is complex and highly politicized. The surplus process allows the creation of TIF districts to act as a sort of stealth property tax that goes towards funding government operating costs rather than the development of the areas the district was created to revitalize.

Although this year’s $1.01 billion surplus is the largest in Chicago’s history, the oncoming expiration of many TIFs beginning in 2030 means that surpluses will begin to decline. As more TIF districts expire, local governments will be unable to rely on TIF surpluses to provide revenue increases. The City and its sister agencies should beware of counting on TIF surplus revenue in future budgets – eventually, it will not be there.

References

[1] Determining exactly which TIFs fall into each region of the City requires broad categorization. For the purposes of this report, the downtown area is bounded by the Eisenhower and Kennedy expressways, as well as the Chicago River. The boundary between the North and West sides was the Kennedy expressway and W North Ave. The boundary between the West and South sides was the Stevenson expressway. Some TIFs cross these boundaries and were categorized into the region with the largest geographic share of the TIF.