November 20, 2020

Illinois has lost less tax revenue than expected this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the State still faces a significant budget gap, according to the latest official projection.

The Governor’s annual economic and fiscal policy report, issued on November 13, raised the projection for the current year’s general operating revenues by $2.2 billion from the July forecast. However, even with the additional revenue the State projects a budget deficit of $3.9 billion in fiscal 2021, which ends on June 30.

Without additional federal relief or changes to State taxes and spending, the budget gap is expected to grow to $4.8 billion in FY2022 and remain over $4 billion through FY2026. As a result, the State’s backlog of unpaid bills could grow from $10.2 billion at the end of FY2021 to $33.2 billion in FY2026 if policies remain unchanged.

Governor J.B. Pritzker had hoped that the federal government would provide funding to offset the pandemic-related revenue shortfalls of Illinois and other state and local governments, but Congress has been deadlocked over such relief. As an alternative, Illinois’ enacted FY2021 budget authorized $5 billion of borrowing from the Federal Reserve’s Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF), an emergency lending program that allows states and large local governments to borrow at interest rates slightly below market rates for up to three years. The administration is still considering a “prudent level” of borrowing from the MLF, according to the November report, which also acknowledged that repayment would further strain the State’s finances. The program is scheduled to expire at the end of the calendar year, and the Treasury Department has declined to extend it. Governments are required to submit their borrowing requests by December 1.

The FY2021 budget had also counted on about $1.3 billion in new revenue from a constitutional amendment to permit graduated income tax rates, but the change was rejected by voters on November 3. As a fallback, this year’s budget included the sale of bonds authorized in 2019 to reduce the State’s backlog of unpaid bills. However, the backlog bonds are not mentioned in the new report as a way to address the operating deficit, and budget officials said in an email that the administration is seeking to minimize borrowing.

Illinois is among a number of states that have reported better than expected tax revenues in the current year. As previously discussed in this post, initial forecasts of devastating state revenue shortfalls due to the pandemic may have turned out to be too pessimistic because this recession differs in many ways from past recessions.

A recent Brookings Paper determined that state income tax revenues have been boosted by the federal government’s generous fiscal support of businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and greatly expanded and taxable unemployment benefits. In addition, unemployment during the pandemic recession is unusually concentrated among low-wage workers, who pay less income taxes than higher wage workers, while a rebound in the stock market has sustained taxes on capital gains. The analysis also concluded that the drop in sales tax collections may be less than originally predicted because of the disproportionate decline in the consumption of services, which are mostly untaxed in the United States.

The Illinois Governor’s Office of Management and Budget (GOMB) offered its initial estimate of the pandemic’s impact on April 15. Base General Funds revenues (before borrowing or revenues from the proposed graduated income tax) were projected to decline by $4.4 billion, or 10.7%, to $36.3 billion from $40.7 billion in the Governor’s recommended budget on February 19. The three largest State-source revenues—individual income taxes, sales taxes and corporate income taxes—were expected to decline by 8.8%, 17.5% and 17.8%, respectively. At that time, the FY2021 budget deficit was projected to be between $6.2 billion and $7.4 billion, depending on whether the graduated income tax structure was approved. As explained here, the deficit forecast was based on the estimated revenue shortfall, the Governor’s recommended FY2021 spending level and the need to repay a total of about $1.6 billion in short-term borrowing from FY2020. About $1.2 billion of the borrowing was from the MLF and was needed due to the extension of the income tax filing deadline from April 2020 to July 2020, which deferred payments to the following fiscal year.

In the State’s FY2020 fourth quarter revenue report in July, GOMB raised the base revenue forecast for FY2021 by $436 million to $36.8 billion from the April projection of $36.3 billion. Although both individual income tax and sales tax collections had come in higher than expected during the spring, only the sales tax projection was increased. GOMB raised the sales tax forecast by $393 million, or 5.3%, $7.8 billion from $7.5 billion in April. The July report attributed the strong sales tax performance to income and price stability that helped support continued consumer spending on durable goods, as well as the growth of online shopping.

The November projection of $39.0 billion in base revenue includes a combined increase of $1.8 billion in all three major revenue sources from the July forecast: $1.2 billion, or 6.4%, for individual income taxes; $364 million, or 4.6%, for sales taxes; and $299 million, or 14.7%, for corporate income taxes. Since the initial forecast of the pandemic’s impact in April, the base revenue estimate has risen by $2.7 billion, or 7.4%. The latest projection represents a decrease of $1.7 billion, or 4.1%, from the pre-pandemic forecast in February. That compares with the 10.7% drop projected in April. The positive effect on the FY2021 budget is offset mainly by the elimination of revenue from rejected graduated income tax structure.

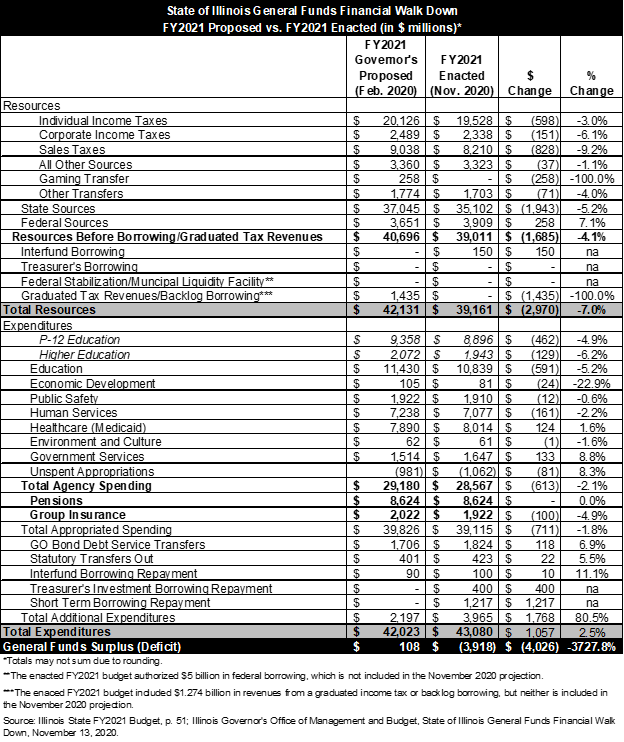

The following table compares the FY2021 General Funds budget proposed by the Governor in February with the budget approved by the General Assembly and enacted in June. The enacted budget in the table uses the new revenue forecast from November. The legislature’s budget was balanced with $5 billion in federal borrowing and $1.3 billion in graduated income tax revenues (or backlog bonds), but those resources are not included in the November numbers. Before the pandemic, the graduated tax had been expected to bring in $1.4 billion, net of a $100 million supplemental pension contribution that was not included in the enacted budget.

Enacted FY2021 expenditures of $43.1 billion are $1.1 billion, or 2.5%, above spending of $42.0 billion proposed in the Governor’s budget. Agency spending, which does not include pension contributions or group health insurance payments, declines by $613 million to $28.6 billion in the enacted budget from $29.2 billion in the Governor’s proposal. Appropriation reductions include $591 million for education and $161 million for human services. Those reductions are more than offset by borrowing repayments of $1.6 billion from FY2020. However, agency spending in the enacted FY2021 budget is up by $1.4 billion from an estimated $27.2 billion in FY2020.

To close the budget gap in FY2021, Governor Pritzker said recently that he plans to examine spending reductions before other options. In September budget officials asked agency directors to identify cuts of 5% in the current year and 10% for FY2022. Agencies were previously asked to suspend non-essential spending and limit non-essential hiring. The State currently has about 5,000 vacancies in agencies under the Governor out of a total of 55,491 positions authorized in the FY2020 budget. The November report said the Governor will also work with legislative leaders to find business tax loopholes that can be closed and other tax adjustments designed to minimize the impact on working families.

The General Assembly was scheduled to hold a six-day veto session in November and December, but the session was cancelled on November 10 due to the pandemic. The next legislative session is expected to begin in January. During the veto session bills require a three-fifths majority to take effect immediately, but only a simple majority is needed after the beginning of the calendar year.