June 16, 2025

This report is part of a three-part educational series on what's at stake for CPS in FY2026 and beyond. Click here to view the one-page summary of these reports.

by Daniel Vesecky

The Chicago Public Schools District (CPS or the ‘District’) and the Chicago Teacher’s Union (CTU or the ‘Union’) recently reached a collective bargaining agreement after almost a year of negotiations. The new costs of the contract will add to an already large and growing structural deficit that CPS faces as the July 1 start of the 2026 fiscal year (school year 2025-2026) draws near.

As the CPS Board of Education approaches its FY2026 budget approval deadline of August 29, it faces a variety of unresolved challenges. Despite declining enrollment over the past several years, the District has increased staffing and kept building usage constant, leading to significant underutilization. It also faces large underfunded pension liabilities, high debt paired with a junk credit rating, and a lack of meaningful cash reserves. Combined with the costs of the new collective bargaining agreement and the spend-down of the District’s remaining federal COVID-19 relief funding, these financial challenges have come together to create the large structural budget deficit that CPS now faces.

The District’s estimated projected budget gap for FY2026 of $529 million hinges on several assumptions that are far from certain and in some respects doubtful. The CPS estimate assumes that: (1) the District will receive the same level of TIF surplus funds from the City of Chicago that it received in this year FY2025—a record-breaking $300 million; (2) CPS will not reimburse the City of Chicago for a portion of the municipal employees’ pension fund (more than half of whose covered members are non-teacher CPS employees); (3) the District will not lose any federal funding; and (4) market conditions will allow the District to refinance outstanding debt to save $100 million in interest costs. Further, the school-level budgets that CPS introduced to principals in May 2025 also assume that the District will receive an additional $300 million in unused Tax Increment Financing (TIF) surplus funds from the City of Chicago, on top of the $300 million already assumed. This assumption, which has no precedent, would decrease the deficit from $529 million to $229 million.

These factors all beg the question: are CPS’ budget assumptions realistic? Given the above overly optimistic assumptions, the deficit could easily run significantly higher than $529 million. The fact that TIF sweeps are not a guaranteed source of revenue and that the size of sweeps vary from year to year means that the starting structural budget deficit for FY2026 is really $829 million—$300 million above the stated $529 million. Any changes to the other assumptions would knock the deficit up even higher. Finding long-term, structural solutions to the District’s current financial challenges will be imperative number one for the Board of Education as it works to adopt a balanced budget for the upcoming fiscal year.

The District has very few readily available options for generating new revenue and may be forced to cut spending if it is unable to arrive at a balanced budget plan. This report will unpack what is in the new teachers’ contract, what the District’s current deficit looks like, and what the CPS’ options are as it begins its FY2026 budgeting process.

The Teachers’ Contract

The Chicago Teachers Union secured a number of changes in the new contract approved in April 2025, including pay increases and more prep time. What follows are the highlights of the agreement, which runs (retroactively) from July 1, 2024 through June 30, 2028.

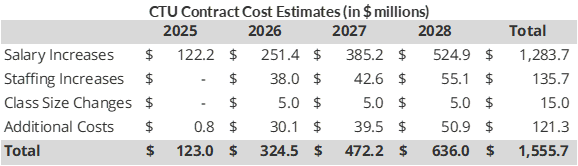

Based on a memo from CPS leadership to the Chicago Board of Education, when costs for all the contract provisions are summed, the District expects additional costs of $123 million in the current FY2025 budget, with substantial jumps to $324.5 million in FY2026 and $472.2 million in FY2027. The final year of the contract, FY2028, is expected to cost $636 million. All told, the changes in the agreement are expected to incur costs of $1.56 billion for CPS over the four-year period of the contract.

Salary Increases

The costliest issue in contract negotiations was pay increases for CTU members. The Union initially requested pay increases of up to 9% annually to compensate for increases in the cost of living. Eventually, the contract settled for a 4% cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for the first year of the contract, followed by 4-5% increases depending on inflation in future years. However, tenured teachers will get COLA increases of up to 7.5% in the first year of the contract and up to 8.5% in future years, depending on their years of service. COLAs and other pay increases included in the contract, such as special bumps for long-serving teachers, are estimated to increase average teacher salaries from approximately $86,000 to over $100,000 by the end of the contract. These salary and benefit costs combined are expected to cost $122.2 million in FY2025, and total $1.28 billion over the life of the contract, which runs through FY2028.

New Hires

CPS has hired about 7,000 new teachers and staff members since 2020, funded primarily through the influx of temporary federal COVID funding, though many of the additions were required under the preceding collective bargaining agreement. The new contract commits CPS to hiring an estimated 800-900 additional staff members over the next four years. According to CPS, most of these hires will serve students with disabilities, English learners, and other high-need students. The contract also reduces the student-teacher ratio for case managers of disabled students and English Language Program Teachers, thus requiring the District to hire more of each role. Finally, the contract calls for the District to hire an additional 30 librarians each year and assign at least one nurse and one social worker to each school by the end of the contract. CPS expects that the new staffing will cost a total of $135.7 million through FY2028.

Increased Prep Time

Prep time for elementary and middle school teachers was a major issue of contention during negotiations. CPS was unwilling to sacrifice instruction time to add to prep time, while CTU demanded up to an additional 30 minutes of daily prep time. Under the previous contract, elementary and middle school teachers already got 330 minutes of prep time a week – an hour a day, plus two additional 15-minute periods weekly. Even prior to the new contract, this amount significantly outpaced the average prep time afforded teachers in most peer jurisdictions nationally. Under the new contract, prep time will increase to 350 minutes. The change was made by removing the two 15-minute floating periods and replacing them with an additional 10 minutes a day. This will not reduce instructional time, but different schools will see the increased time implemented in different ways, with some schools extending recess to comply with a state law requiring a minimum of 30 minutes of play time in all elementary schools and others extending specialty classes such as art and music to give homeroom teachers more time to prepare. Several professional development days that were previously directed by principals will also now be teacher-directed, with the goal of creating more focused prep time on these days.

Reduced Maximum Class Sizes

Although CTU won lower minimum class sizes in its 2019 contract, there were limited mechanisms for enforcement. The new contract establishes class size minimums that are lower than the previous contract, dedicates $40 million to supporting the lower sizes, and requires that any class that exceeds the minimums automatically have a teaching assistant assigned to it. The new class size limits are:

- 25 students in kindergarten, down from a limit of 28

- 28 students in grades 1-3, the same as in the previous contract

- 30 students in grades 4-8, down from 31

- 29-31 students in grades 9-12

Changes in class size are expected to cost $5 million per year starting in the 2026 fiscal year, for a total of $15 million throughout the life of the contract.

Changes in Evaluations

Currently, all CPS teachers go through an evaluation cycle every two years. CTU pushed to elongate that cycle to three years in recent negotiations. While the District will still require most teachers—all those rated “proficient” in their evaluations—to continue undergoing evaluations every two years, the Union won some exemptions. Teachers who are currently rated as “excellent” and who retain that rating on their next evaluation will only be required to be evaluated every three years going forward. The same will be true for “proficient” teachers who have 19 or more years of experience.

Other Clauses

The contract contains a variety of other agreements, including:

- 50 additional sustainable schools, which partner with community organizations to provide wraparound services.

- Additional funding for athletic staff and programs.

- Network-based fine arts positions to serve schools without art teachers.

These additional costs are estimated to total $121.3 million through FY2028.

The Budget Deficit

CPS faces an estimated deficit of $529 million in FY2026, which is likely to grow in future years as the significantly backloaded costs of the teacher’s contract come to fruition. The District’s budget deficit is structural, meaning revenues are regularly insufficient to meet rising expenditures, resulting in the District needing to use non-recurring sources of revenue to plug budget holes.

The current estimate of $529 million, produced by the District itself, makes several assumptions:

- CPS will not pay for the controversial Municipal Employees’ pension fund reimbursement to the City.

- The federal government will not cut any of CPS’ current funding.

- The District will be able to restructure some of its debt favorably to achieve budgetary savings.

If any of these assumptions prove incorrect, the projected deficit, already large, could balloon further.

Potential Costs

In addition to existing operational costs and the new costs added by the contract, CPS faces several potential risks, such as additional costs or loss of revenue, that are not accounted for in existing projections and would further raise next year’s deficit.

MEABF Repayment

Non-teacher employees of CPS receive pensions through the Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund (MEABF), which was established by the City of Chicago to cover certain city and sister agency employees. Although the MEABF provides pensions to both employees of the City and of other local governments, the City is statutorily obligated to cover all of the pension fund contributions. This arrangement was unchanged until 2020, when the District began reimbursing the City for a portion of the cost accrued by its employees. This stopped in FY2024 when CPS declined to make the $175 million reimbursement. The District’s FY2026 budget assumes that it again will not reimburse the City for MEABF costs. However, this decision depends on the Chicago Board of Education, half of which was appointed by Mayor Brandon Johnson, who is publicly in favor of the reimbursement. It remains unclear whether the District will ultimately choose to compensate the City for MEABF costs in FY2026, but if it chooses to do so, this would add about $175 million to the existing deficit.

The issue of how to handle this reimbursement remains unresolved between the City and CPS and is a significant piece of the disentanglement work to be effectuated before CPS governance becomes completely separate from the city in January 2027. You can read more about the District’s pension funds at the Civic Federation’s recent pension explainer.

Federal Funding Cuts

CPS’ current deficit projections do not assume any substantial changes in federal funding. The District receives nearly $1 billion in federal funding annually. Approximately $494 million – about half of CPS’ federal funding – is dedicated to programs under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). These funds are intended to help schools establish programs for low-income, neglected, and struggling students. Another $110 million supports the District’s implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which funds special education programs. Approximately $211 million is dedicated to child nutrition programs, predominantly dedicated to providing free school lunches and breakfasts to students. Finally, the District receives $100 million in Medicaid reimbursements for medical care provided to students.

Although none of this funding has yet been reduced or cut, the current federal administration has indicated an interest in reducing federal support for local school districts and for Medicaid and has singled out CPS for investigation. If federal funding is cut, CPS will be forced to either eliminate the programs supported by that funding or redirect its existing revenue to cover the budget holes, thereby enlarging its deficit.

Debt Restructuring Uncertainty

The FY2026 projected deficit includes the assumption that CPS will be able to save $100 million through bond refinancing. If market conditions are optimal, it may be possible for the District to refinance existing high-interest bonds and replace them with bonds that carry lower interest rates, thus saving CPS money on interest payments. Successful bond refinancing carries no economic downsides for the District, as long as the repayment schedule remains the same, and purely results in savings due to lower interest rates.

Debt restructuring is a good way for the District to achieve financial savings, but only when it is done truly for financial benefit rather than delaying debt repayments (a tactic known as “scoop and toss”). However, the projected savings from restructuring debt depend on favorable market conditions for refinancing. Such conditions are never a given and are made less likely by recent market fluctuations and widespread uncertainty. In addition to stock market fluctuations, municipal bond markets have recently seen sharp increases in bond yields, meaning that interest rates for municipal bonds are rising. This makes it less likely that CPS would be able to successfully refinance under current market conditions, especially given the District’s junk-status credit ratings. If CPS is unable to refinance its debt this year, the $100 million in projected savings would instead be added on top of the projected $529 million deficit. Further complicating the outlook are recent national bond market volatility and weakness, unfamiliar yield curves, and the recent “negative outlook” issued by Fitch Ratings for the City of Chicago, with which CPS is still financially and legally intertwined. These factors further dampen the likelihood that CPS will achieve the refinancing savings it has assumed in budget projections.

Charter School Costs

In addition to the assumptions above, a recent decision by the Chicago Board of Education related to charter schools could increase expenses. In February, the Board voted to keep open five of the seven Acero charter schools slated for closure next year. In order to do this, the District will need to spend approximately $3 million next year, and an additional $21-$28 million to convert them into District schools. The ultimate cost of the conversion may fluctuate depending on how many schools the District decides to convert, but the final bill will likely be above $20 million. The current deficit projection does not account for these costs.

Potential Revenues

The District does not have many revenue options to reduce the deficit. Its three main revenue sources—property taxes, state funding, and federal funding—are either largely tied to formulas, such as the State’s evidence-based funding (EBF) formula, or are limited in annual growth. The only certain method CPS has of increasing its revenue is raising its property tax levy to the statutory limit, a move that is already assumed in the deficit projections. Of the remaining revenue options CPS has, some are more politically or logistically feasible than others. Some revenue sources, like asking the State of Illinois for additional funding, are unlikely given the state’s own fiscal challenges and certainly will not happen in time to plug the FY2026 deficit. However, these sources are still worth examining, as the District is likely to face increasing structural deficits for the next several years.

Property Tax Revenue

CPS primarily raises its own revenue (as opposed to revenue received through state and federal funding) through property taxes. The District routinely raises its property tax extensions to the maximum amount allowed by the PTELL law, which limits property tax increases to the lesser of 5% or the rate of inflation, although there are numerous exceptions. The District’s projected deficit assumes that CPS will raise the maximum allowable property tax levy again in FY2026 and capture additional revenue from new or improved property value and expiring TIF districts. These sources are projected to generate a combined increase of $230.8 million in property tax revenue in FY2026, which is already factored into CPS’ projected deficit. In order to raise additional property tax revenue, the District would need to initiate a referendum to raise the tax extension higher than the limit. Due to the amount of time organizing a referendum would take, this solution may not be able to plug the budget gap in FY2026, but it could prove important in stemming future deficits.

CPS also benefits from an additional special property tax levy whose revenue stream is dedicated to paying part of its pension obligations. This pension levy is not subject to the tax caps under PTELL and instead is applied using a flat rate.

As a longer-term option, CPS might pursue instituting an additional tax levy similar to the property tax levy for teacher pensions. For example, it could levy a tax specifically for the purposes of paying pension obligations to the MEABF, servicing debt, or covering maintenance costs. However, it would need authorization from the state legislature to do this.

Additional City Funding

As an immediate way to alleviate pressure on CPS, the City of Chicago could agree to suspend its pursuit of the reimbursements from CPS to the City for the MEABF pension fund payment in FY2026. However, this would increase the more than $1 billion projected budget deficit in the City of Chicago’s own FY2026 budget.

One major way the City of Chicago has provided direct funding to CPS in recent years is through Tax Increment Financing (TIF) surplus funds. TIF surpluses are non-obligated funds held by the City’s TIF districts, which are supposed to be used to support economic development, that the City annually might direct for transfer to the City of Chicago and its sister agencies. The size of TIF surpluses varies year-to-year, and is distributed pro rata among the taxing bodies in proportion to their property tax levies. CPS gets approximately 55% of any declared surplus. TIF surplus is considered a one-time revenue source because it is neither guaranteed nor reliably the same amount from year to year.

CPS is urging the City to provide added assistance by releasing a massively larger TIF surplus in FY2026. CPS for the past year has been stating the FY2026 budget deficit projection of $529 million. That figure assumes that CPS will get approximately $300 million in TIF surplus revenue—the same level it received from the City in FY2025. What that means however, is because TIF surpluses are non-guaranteed revenue, the district’s actual projected starting deficit is $829 million. CPS is assuming that the City will declare a minimum total TIF surplus equal to the record surplus the City of Chicago declared in FY2025—about $570 million. In addition to that amount, CPS’ preliminary budgets released to schools this spring assume the City will distribute an additional $300 million in TIF surplus funds to CPS—$600 million total, or double the prior year’s record amount. Based on this assumption, CPS estimates a reduction in the deficit to only $229 million. However, the uncertainty of the size of TIF surplus makes this estimate highly unreliable and unrealistic given the enormous jump it is assuming. Moreover, the size of any surplus funds sweep is decided entirely by the City, not CPS, and that contingency depends on how much unobligated money is held in TIF accounts. TIF surpluses are also not announced until the fall, which means that CPS will have to pass a budget before knowing how much TIF surplus funding it will receive. Not receiving the additional $300 million would balloon the current deficit projection by that amount.

Additional State Funding

The State of Illinois provides funding to all Illinois school districts based on an evidence-based funding (EBF) formula. The EBF formula, instituted in 2017, was transformative for CPS. It made State contributions regular and predictable and provided CPS with a large inflow of funding. The State also now covers 35% of CPS’ annual contribution to the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund. Although CPS is requesting additional support from the State, Illinois is facing its own budget challenges this year, making it highly unlikely that it will be willing to provide CPS with additional funding. However, there are several areas in which the State could provide more support to the District, if it chose to do so.

First, the State could pick up a larger share of the District’s pension payments. Currently, the State of Illinois only covers approximately 35% of annual pension costs for CPS, as opposed to 97% of pension costs for all other school districts in the State. This obligates CPS to expend hundreds of millions of dollars annually on pension funding. CPS has a property tax levy dedicated specifically to pension funding which covers most of the CPS employer contribution. However, when this levy is not enough to cover the full contribution, which is usually the case, the District has to pull pension funding from its general operating funds. If the State were to cover a larger share of the pension costs, this would free the District to shift that money to operational spending, offsetting the deficit. The most likely path for the State to provide additional pension support would be to consolidate the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF) with the rest of the State’s Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS). Past conversations about consolidation have been complicated by two things – the spread between the funding levels of the two systems and the willingness of CPS or the CTU to turn over management of the CTPF fund to the State as part of any consolidation or leveling of state subsidization. However, today both funds are at similarly funded ratios and therefore the funding spread is no longer as much of an impediment. The second impediment may require extensive negotiation.

Second, another source of possible state funding is additional funding to through the evidence-based funding formula, a solution urged at various junctures by the CTU, the City, and CPS. The EBF’s goal is for every school in the State to be funded to 90% of adequacy by FY2027, but CPS is currently only bunded at 80% of adequacy and the current schedule of EBF funding will not satisfy this goal until FY2034. However, this funding is distributed across Illinois, and state law prohibits special treatment for a single school district. So, to provide CPS with additional support through the EBF would require the State to provide matching levels of support to all school districts across Illinois. Kids First Chicago estimates that if the State were to add an additional $300 million of EBF funding, for example, only $43 million of that would flow to CPS.

Given the State’s current budget concerns, it is unlikely that any type of additional state support will play a significant role in closing CPS’ budget deficit in FY2026. However, the District should attempt to work with the State on future revenue support, as the District’s deficit will continue to grow in the coming years.

Borrowing

One final measure has been made a topic of public debate during the now concluded bargaining round between the CTU and CPS; taking on additional debt to fund operating costs. Borrowing for operational costs is not fiscally responsible and is contrary to fiscal best practices. In addition, CPS has a junk credit rating and municipal bond markets are currently faring poorly. These two factors combined means that any bonds issued by CPS to cover FY2026 operational costs would likely have extremely high interest rates, which would close the current budget deficit but create higher budget gaps in future years. Moreover, borrowing for operating costs would risk further lowering of CPS’ junk status credit rating, with potential spiraling consequences that may begin to constrict its access to credit markets. As this was one of the conditions in the late 1970’s that led to the institution of a School Finance Authority in 1980, the Civic Federation strongly recommends that CPS not take on additional debt to close the FY2026 budget gap.

Cutting Costs

Even if all the District’s favorable assumptions prove correct and it is able to find some additional streams of revenue, it is unlikely that CPS will be fully able to eliminate the $529 million deficit in FY2026. Therefore, to balance the budget, the District will likely have to institute spending cuts, the scale of which will depend on the ultimate size of the deficit.

About half of the District’s $10 billion budget is not discretionary spending. This includes spending on pension obligations, debt service, charter school tuition, and spending restricted through grant funding. Due to legal obligations and restricted funding sources, this spending cannot be cut or redirected. That leaves about $5.3 billion from which to make spending reductions. If, for example, the District were to be faced with the $529 million deficit it projects, then it would have to cut discretionary spending by approximately 10%. According to CPS projections, this would involve cutting at least $200 million in direct school funding, $250 million for district-wide school support such as maintenance and technology, and $20 million in central office administrative cuts. The blow to direct school funding would likely be felt immediately, with major cuts to discretionary funding within the budgets of individual schools and larger class sizes, which would lead to layoffs projected to reach above 1,600. Reductions to support and administration, in contrast, could have effects that are felt over time, as deferred maintenance and lower administrative capacity lead to inefficiencies. If Board commitments, federal cuts, or other circumstances increase the deficit above the $529 projection, these cuts could become even deeper and would have a severe impact on the quality of education provided by the District.

Conclusion

There is no simple solution to the problems facing CPS. As previously stated, the District’s deficit is structural, meaning that the annual budgets regularly do not have enough revenue to match rising expenses, resulting in the use of one-time revenue sources such as federal COVID funding and TIF sweeps. While the District achieves technically balanced budgets, they rely on non-recurring revenue sources and fail to find long-term solutions. The size of the structural gap will only increase in future years due to the new teacher’s collective bargaining agreement.

Any fix to CPS’ structural deficit will require structural solutions. This will mean right-sizing District operations to align costs with stable and sustainable recurring revenues. Among other options, the District could continue to decline to cover MEABF payments, work with the already cash-strapped State of Illinois to provide additional funding support, or hold a referendum to raise property taxes, which the District is already highly reliant on. The District could also consider cutting costs and rightsizing areas of spending that do not align with its current enrollment numbers, which have been falling for years. None of these solutions are optimal, and each one will negatively impact some stakeholder groups. However, working to solve the deficit immediately will provide CPS with a much higher chance of success than continuing to kick the can down the road. Failing to address the structural deficit now could force the District to enact massive spending cuts, or to take out short-term debt which would be highly expensive, result in lower credit ratings, and restrict future spending due to high debt obligations. The Board of Education must act now to stave off the mounting threat of future financial collapse.

This research was supported in part by the Joyce Foundation. The Civic Federation is a nonpartisan, independent research organization, and the views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the Joyce Foundation.